The scientific foundation of the the so-called no-vax campaign is obscure at best, the result of beliefs not supported by empirical evidence.

Unconfirmed beliefs versus the scientific method has been a long and tough battle. Is it possible for science to win it? One powerful weapon on the side of science is allowing scientific research to be based on open access to data and methods, to allow for the results to be reproduced by others and then, to make those results understandable to as many people as possible.

The main steps of scientific research, as I have been taught, can be summarised as follows: observation of a phenomenon and its evolution; the collection of data, along with external interventions, potentially affecting the phenomenon under study; implementation of an appropriate method for the analysis of the data at hand; investigation of the cause-effect relationship, bearing clearly in mind the timeline of events to identify and track causes and effects properly.

Through a very large number of widely accepted research studies, it was learned that vaccines play a fundamental role in the containment of potentially devastating illnesses. Because of vaccines, diseases such as poliomyelitis (polio), tetanus, diphtheria have been nearly eradicated in large areas of the western world. The last case of poliomyelitis reported in Italy was in 1982, 40 years ago — a consequence of a massive vaccination campaign.

Does it mean that poliomyelitis has disappeared completely? No, but its spread is substantially reduced and the vaccination campaigns have made the disease a very rare event in the western world. This rarity of cases has had a strong impact on the collective perception of risk, contributing to the birth of the belief that “the vaccine is not needed; polio is no longer here.” Educated people, sometimes, refuse the vaccine based on this motivation. The effect (no cases) is seen regardless of its cause; the success of the vaccine is taken as evidence that the vaccine is not needed.

The disease, however, is not eradicated. It is present at a higher rate in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan, and outbreaks also occur in other countries such as Guinea, the Democratic Republic of Laos, and Madagascar. Polio cannot just be forgotten by the human species — it is such that 5% to 10% of children who contract it die from paralysis of the respiratory muscles, while adult lethality is between 15-30%. It often leaves serious consequences, such as paralysis of a limb.

A similar phenomenon occurs with a more recent disease, COVID-19. Use of social distancing and masks have been found to be effective at containing it. The mask blocks the droplets that can carry the virus from one person to another. It has been estimated that if 80% of a population wore masks constantly, it might not be necessary to quarantine entire nations. Still, there is a very strong movement against the use of masks in some countries. In countries like Italy, where the containment of the virus has been particularly effective and masks were commonly used together with social distancing starting from the end of the lockdown (May 4 2020), we often hear people say, “the virus is gone, what is the use of a mask.” The effect (fewer cases) is again seen regardless of what caused it. Like with vaccines, the successes associated with masks are taken as evidence that masks are not needed.

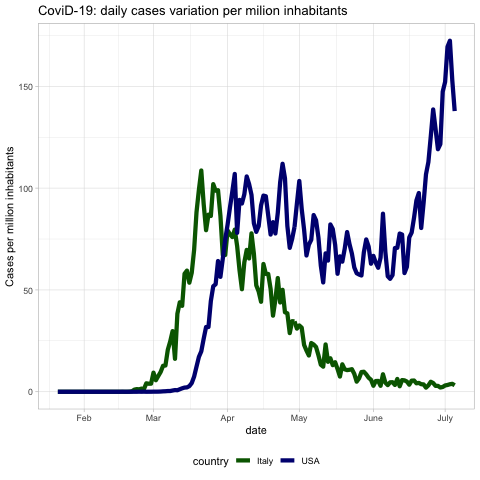

To this cognitive bias, let us add the fact that political opinions may also influence decisions about whether to social distance and wear masks. It can be easy for humans to trust politicians and/or television experts who are saying things that already align with their feelings or beliefs, even if the words are not supported by empirical evidence. Similarly, are we driven by a belief that the virus may be contained using masks? Well, we can see the association between neglecting the usefulness of masks and social distancing to containing the virus starting from a simple descriptive analysis. Just as an example, let us look at the trajectories of new reported cases per million inhabitants in the USA compared to Italy from January to the end of June 2020.

The contagion started in Italy a little earlier than in the US, though after the start several containment measures were applied in both countries (lockdowns, social distancing, compulsory use of masks). As a consequence, the spread of the virus slowed. The Italian government maintained the containment measures for a long period and still publicly supports the use of masks in our daily life activities. In most of the states of the US, many people stopped using caution and did not adopt mask wearing after reopenings (though that is changing now with some mandatory mask orders). As of mid June, the number of new cases started growing again, consistent with the beginning of the epidemic, or worse. Although one cannot isolate the effect of mask-wearing from the many differences in policies and behaviors between these countries, the trajectories seen in the graph certainly suggest that mask-wearing can contribute to containment.

Both examples can be explained by the cognitive biases contributing to an effective-intervention paradox.

And now, as we await development and approval of a vaccine in this pandemic, there are real questions about the effects no-vax campaigns may have on efforts to vaccinate against coronavirus. It is important to understand potential reasons for the no-vax information, as well as how the information spreads, as described in this 13 May 2020 article in Nature: Anti-vaccine movement could undermine efforts to end coronavirus pandemic, researchers warn.

The short memory of humans, as a collective individual, leads to forgetting what caused the present situation — effects are temporally exchanged with what caused them. A stronger education in the basic principles of science seems to be the only way to remove this bias.

More from the StatGroup-19 blog at https://statgroup-19.blogspot.com/.