While most state leaders worldwide are busy securing a supply of COVID-19 vaccines, almost half of the Filipinos are reluctant to get vaccinated according to Pulse Asia Survey conducted from 23 November to 2 December 2020. This is a bit higher than the September 2020 report from Social Weather Stations survey showing only about 31% of Filipinos would refuse COVID-19 vaccines.

According to Pulse Asia, the safety of COVID-19 vaccines is the top concern of Filipinos who had a negative response to the idea of getting vaccinated. Some analysts attribute this phenomenon to Dengvaxia controversy. This happened around early 2018 when vaccinated children who had not been infected with dengue became more at risk of “developing severe dengue.” And then, another news story came up recently headlined “A ‘healthy’ doctor died two weeks after getting a COVID-19 vaccine.” There are two terminologies that we often encounter when we hear news about vaccines: safety and efficacy. When vaccines are deemed safe, does it follow that it is effective, or vice-versa?

On vaccine’s safety

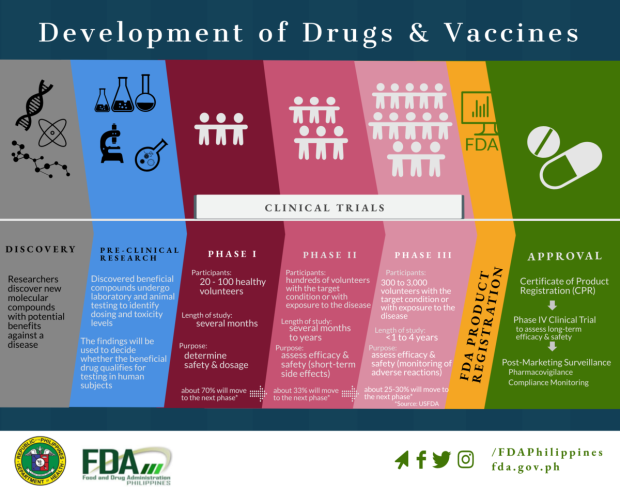

Vaccines are a product of collaborations of great minds using appropriate facilities to create safe and effective drugs. Scientists first subject a new vaccine to randomized controlled trials in the laboratory. If the drug passes the laboratory testing, it undergoes three phases of clinical trials in humans illustrated below.

After the phases of human clinical trials, pharmaceutical companies will have the general authority for food and drugs in a country examine the potential vaccine. If time and resources permit, some even conduct a Phase IV clinical trial. Although for COVID-19 vaccines, the FDA Philippines released a circular on December 14, 2020 about the Issuance of Emergence Use Authorization (EUA).

This only demonstrates how rigorous the development of a vaccine is. Of course, there might be some side effects associated with the vaccine that can happen inside a person’s body just like in any other drugs (yes, all other foods and drugs in the market have potential risks to us too). However, scientists use the best available resources to design a vaccine as harmless as possible to humans through repeated observations and clinical trials.

In a sense, this is like statistical hypothesis testing. Scientists are trying to minimize the chance of concluding that the vaccine is deemed safe (i.e., following FDA criteria or having tolerable effects on the individual) when in fact it is not safe or has serious effects on the body. This can be seen as analogous to committing a Type I error in context of null hypothesis testing; In this case the null hypothesis is “the vaccine is not safe” and the alternative is “the vaccine is safe.” Scientists also want to minimize the chance of concluding the vaccine is not safe when in fact it is safe (analogous to a Type II error).

The consequence of committing a Type I error is vicious because an unsafe vaccine is given to individuals. On the other hand, the consequence of committing a type II error is not only waste of resources (formulating another vaccine when in fact we already have a “safe” vaccine) but most especially, delaying the vaccine could mean continued high rate of illnesses and deaths that were preventable. We know there is a tradeoff between the error rates (lowering one increases the other) — hence, tests are often formulated to have a lower rate for the error with greater consequence. In this case, both errors have serious consequences, however, we also want to avoid doing harm by giving the vaccine. Part of the role of the FDA is to be transparent to people about the possible consequences of these errors in decision making and maximize the vaccine’s safety and efficacy to its constituents.

Aside from safety, another issue that hit the social media was about the nurse who got vaccinated and then tested positive for COVID-19 a few days later after working in a COVID-19 unit. I read some comments saying that these vaccines might not be that effective, but it depends on the length of time after vaccine, dose, exposure, etc. This one case publicized by the media should not be taken as broad evidence of lack of effectiveness, as the nurse may have had contracted the disease before the vaccine was expected to take effect (about 10 – 14 days).

COVID-19 vaccine efficacy

What do we mean when we say that vaccines are effective? And even if our bodies can tolerate the effects of the vaccine, but it is not so effective, can we say that vaccine is still safe? Borrowing the definition of Singal et al. (2014), “Efficacy can be defined as the performance of an intervention under ideal and controlled circumstances, whereas effectiveness refers to its performance under ‘real-world‘ conditions.” The intervention in our discussion here is the vaccine.

In other words, efficacy is the measure of the superiority of the intervention compared to a baseline in a highly controlled set-up, while effectiveness is the capacity of the intervention to deliver the desired outcome in the “real-world” scenario (outside the laboratory). These two terms have different technical definitions, but they are intertwined. A vaccine shown to be effective in laboratories and randomized controlled trials is expected to be effective when deployed in public.

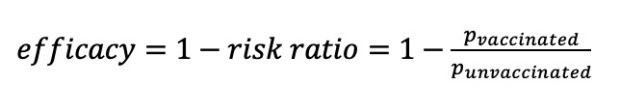

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), efficacy is computed as 1 – risk ratio. The estimated risk ratio is the proportion of individuals in the vaccinated group who became infected (pvaccinated) divided by the proportion of individuals in the control group who became infected (punvaccinated). We want the risk ratio to be as close to zero as possible, meaning the proportion infected in the vaccinated group is low. And, even if it’s not close to zero, we want it to be less than 1 (indicating less infection in the vaccinated group than the control).

Using an estimated risk ratio, a number describing efficacy can be calculated by subtracting the risk ratio from 1.

So, when the risk ratio is less than 1, efficacy is positive (vaccine performed better than the control) and we desire an efficacy close to 1 (corresponding to a small risk ratio due to a low infection rate in the vaccinated group). The efficacy is “interpreted as the proportionate reduction in disease among the vaccinated group”(CDC, 2012).

The BBC news released a comparison among the COVID-19 vaccines. The best performing vaccine in terms of estimated efficacy is the mRNA technology of Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech, at around 0.95 given data so far (or 95%). This technology is very outstanding. However, it needs to be stored in -20 C to -70 C, which is much lower than the average fridge temperature of -18 C. For a very tropical country like the Philippines, we will need special facilities for the importation and distribution of this vaccine. Sinovac and Gamaleya, on the other hand, have regular fridge storage which will save us some cost, but that comes with lower efficacy.

Vaccines are important

We cannot impose vaccines on anyone, especially in a democratic country like the Philippines, but knowing the proportion of individuals who are willing to get vaccinated is important for national immunity. If most of the population has immunity against the virus (which is the principal purpose of the vaccine), the spread of the virus can be contained because an infected individual will have a very low probability of infecting another individual a.k.a., herd immunity. This translates into low hospitalization and mortality rates due to COVID-19. A few examples of vaccine successes given by D’Souza and Dowdy are measles, mumps, polio, and chickenpox. These diseases were deadly and very contagious pre-vaccine, but after the development of vaccines, the community achieved this so-called herd immunity.

With or without the vaccine, the risk is always there; it is not just for individuals, but for world health in general because even though our vaccine today is considered safe for individuals, the virus can still transform into a more potent form that can greatly reduce the effectiveness of the vaccine. On the other side of the coin, if the efficacy of the vaccine remains and it works the way we hope it will, this pandemic due to COVID-19 may be terminated – we can lessen many health protocols and finally see each others’ faces outside our screens. COVID-19 can just be like any other seasonal flu on the planet - sure, it may not disappear totally, but humans will learn how to manage it. Nevertheless, just like what Prof. Nazareno (from University of the Philippines Los Baños) said, humans should not stop searching for ways to completely eradicate COVID-19. statThe decision of which and how much risk we are willing to take as an individual is still up to us.